The True Danger Isn’t Dictators — It’s Our Indifference

Today I told someone that I felt nervous about the state of the world. It’s not like me to worry the way I have been lately, but the news has truly unsettled me.

As if the events in Venezuela weren’t enough to rattle me, now we’re confronted with two more possible scenarios: the invasion of Greenland and the halt of the midterm elections. I shared my fear about the erosion of democracy and world peace. The person I spoke to replied, “Well, I agree — an invasion of Greenland is ridiculous. It shouldn’t happen. Just like kidnapping a foreign leader shouldn’t happen. It’s wrong. But it doesn’t affect my life, so I don’t worry about it.”

I can’t fully describe what I felt when I heard those words. I was stunned. And then, after sitting with it, I realized I had just encountered the true danger. The greatest threat to democracy — to humanity — isn’t the dictator, the authoritarian, or the violent leader. It’s the absence of caring.

I am well versed in the theories about how evil manifests, how a lack of empathy allows it to flourish. But I’ve always associated those ideas with the darkest chapters of history: the Second World War, the Crusades, slavery, and other horrors committed by human beings. Yes, I’ve written about Sudan, the destruction of the rainforests, the suffering in Palestine, and countless other crises. There is no shortage of malignant behavior in this world.

But today I realized something uncomfortable: my battle against the destruction of humanity has been a safe one. Fought behind my computer, in my warm and cozy office. Focused on distant places and distant people. Today, for the first time, I felt confronted by the absence of caring in someone I know well — someone I respect — someone I never expected to respond that way.

Many have written about this. Plato, perhaps the first, said: Ignorance is the root and stem of all evil. He believed that unawareness of truth, a failure to understand consequences, and the absence of compassion create the conditions for injustice. Knowledge, he argued, is the antidote.

To a large extent, I agree with him. People often hold convictions that aren’t grounded in objective truth, empirical evidence, or even basic knowledge of history or geography. They rely on what others have told them or on their own interpretations. And there’s nothing inherently wrong with that — none of us can know everything. But we can strive to learn more, especially about the issues we form opinions on. The question is: even if we knew everything, would evil disappear?

Plato believed knowledge was the solution. I’m not convinced. Modern thinkers aren’t either. At the Nuremberg trials, the American psychologist Gustave Gilbert concluded that evil is the absence of empathy. A genuine incapacity to feel with another human being.

The atrocities of the Second World War forced us to examine why people stand by and let terrible things happen. Hannah Arendt, the German philosopher, called it the “banality of evil” — the idea that great harm often comes not from monsters, but from ordinary people who fail to think or care about the consequences of their actions.

So is that where we are now? Have we become so disconnected, so consumed by the virtual world, so focused on protecting what we have and chasing what we want, that we simply don’t care about others anymore? Has our capacity to worry about strangers evaporated? In this age of disinformation and noise, have we lost the ability — or the will — to understand the consequences of certain acts?

Are we absolved from evil simply because we don’t know or don’t care?

Think about it. If our indifference contributes to famine, violence, or death, are we truly free from blame? If we shrug when a politician dismantles democratic foundations because it doesn’t affect our personal lives, are we not responsible when a country collapses into chaos?

Building and maintaining a society is, in my view, a collective responsibility. Every one of us is accountable for keeping democratic values alive. We must act when those foundations are threatened. We must help people in need, regardless of faith, nationality, or race. We must protect those facing oppression and violence — even when it has nothing to do with us.

How, you might ask? Writing a blog won’t fix it. Thousands of people are doing that. Awareness matters, but it feels insufficient in times like these. This morning, I admitted how shocked I was by the disinterest in Greenland and other threats. I said that indifference will be our undoing. History has shown it again and again: when we stop caring about others, evil takes charge. A nod and a “yes, you’re right” was polite, but not convincing. My fear is that we won’t care until evil knocks on our own door. And by then, it may be too late.

The truth is: I don’t have an answer. I don’t know what will shake us awake from this corrosion of empathy. I don’t know how to make people care if they don’t. And I certainly can’t control the politicians, the tech giants, the profiteers — those who thrive on the suffering or silence of others.

And yet, every now and then, someone surprises me — someone who does care, who asks questions, who refuses to look away. Those moments remind me that empathy hasn’t vanished entirely. They are small, but they matter.

So I turn to you, dear reader.

Do you care?

Do you know how to make others care?

Or are we all waiting for the knock on the door?

#HumanConnection #DemocracyMatters #ChooseEmpathy #YearOfKindness #RosieGlobal

Do you think indifference is becoming normal? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

The Year of Kindness: Why We Need It More Than Ever

As I open my new day planner for 2026, excitement rises in me. The blank pages feel pure, untouched by the demands of appointments and obligations. They hold the promise that anything is possible, that the future is still wide open, and that our lives are something we get to shape for ourselves. An empty agenda at the start of a new year fills me with optimism and curiosity about what lies ahead.

One hour later, most of the coming month is already filled in, and several appointments for the rest of the year have found their way onto the pages. My heart sinks a little. So quickly, the pristine white space has been claimed by obligation.

And yet, having something to do with your life is its own kind of comfort. Whether you are healthy or ill, human contact is essential, no matter where it comes from. A visit to the doctor’s office offers a brief chat with the receptionist, a moment of engagement with the doctor, and a whiff of fresh outside air. A phone call with a friend reminds us that we belong somewhere. We all need to feel that we matter. Human connection — even in its smallest forms — helps us feel that way.

But there are so many people for whom connection doesn’t work like that. People who feel lost, who live with violence, who are victims of war or warlike acts. For them, the only thing that matters is keeping themselves and their families safe. Anyone who read the news in the first days of this year was confronted with an astonishing number of conflicts, wars, and brutal acts of violence. In a world where peace and kindness are desperately needed, we are falling short.

Even in places untouched by war, many live in troubling circumstances. Rates of depression and burnout are unprecedented. Loneliness continues to rise. Chronic illness affects more people every year.

And then there is the environment. Mother Earth has been under attack for a long time, and she is showing the strain. Global warming, melting polar caps, species extinction, and a rise in natural disasters. Microplastics accumulating in our organs. Rising water levels in some regions and severe shortages in others, both contributing to disease and poor health. The destruction of rainforests… the list goes on.

Despite my naturally optimistic nature, it is becoming harder to hold on to faith in good outcomes. Too many world leaders are not leading but fighting, measuring their worth in military strength. And that strategy still appeals to some — people who need others to fail, to weaken, even to die, in order to feel powerful. People who believe they are chosen, better, righteous in their violence.

Still, I believe there are more people who long for a kinder, more peaceful world. People who would rather invest in human connection than in stocks and bonds. People who want lives filled with meaning rather than strife. I truly believe that those who want peace, love, and kindness far outnumber those who don’t.

As I look out my window, I see an untouched blanket of snow covering everything. Like the blank pages of my planner, the snow is pure and peaceful. Nature is reminding me that beauty still exists in abundance — we just have to look for it. Yes, beauty disappears sometimes, as the snow eventually will, but it always returns. And often, one kind of beauty makes way for another: the first blossoms of spring, sun‑kissed beaches in summer, the warm palette of autumn leaves.

Maybe, just maybe, this year we can try a little harder to notice the beauty around us. The stranger helping an elderly man cross the road. A neighbor offering soup to someone who is ill. A baby’s first smile. Perhaps we could baptize this year as the year of kindness. We could look for random acts of kindness — or grand gestures — and more importantly, we could be the ones who create them.

We could spread the word not through social media, but through conversation. Conversations in public and private spaces that strengthen our human connection. We could build alliances and remind our politicians that we want a peaceful world, one that respects human life, nature, and humanity. We could lead by example, showing that there is another way forward — one where everyone is welcome to coexist and participate, and where we support those who need extra help to do so.

We can help each other find, see, enjoy, embrace, and create beauty in this world.

We can be the purest form of an untouched blanket of snow.

Who’s with me?

#YearOfKindness #HumanConnection #ChooseCompassion #InvisibleStruggles #RosieGlobal

If this resonated with you, share it with someone who might need a moment of kindness today.

Beyond the Epstein Files: Global Accountability and Victims’ Justice

As I write this, the Senate — following the House of Representatives — has just voted to release the Epstein files. Many have rejoiced at this decision, as they should, especially the victims of these horrific events. Yet I fear that the sense of victory may soon give way to disappointment, and in more ways than one.

Who doesn’t remember the endless headlines about Epstein? The interview with Virginia Giuffre, or the surreal spectacle of Prince Andrew — now Andrew Mountbatten — insisting he was incapable of sweating during the period when the Epstein scandal unfolded. Apparently, he manages just fine these days.

We were collectively outraged, and rightly so. Now, after years of waiting, the files are finally being released. But true to my nature, I can’t help wondering: will we find the full truth in these documents, or have certain “uncomfortable” names been carefully edited out? The delay itself raises questions. With so many powerful figures rumored to be entangled in Epstein’s circle, it’s hard not to suspect a tug-of-war over whose names appear.

The deeper problem is trust. In an age of misinformation, biased reporting, and political spin, who can we rely on to verify the authenticity of what’s presented? News is tainted by affiliations, checks and balances are weak, and fake stories circulate freely. Against that backdrop, how can we be sure the Epstein files are complete, unaltered, and truthful?

Even if we set aside conspiracy, will the files deliver what people hope for? From a sensationalist angle — whose names appear, what did they do — or from a legal one — can convictions follow — disappointment seems inevitable once the headlines fade.

What troubles me most is not the public’s letdown, but the victims themselves. Victims of Epstein, yes, but also the countless others caught in the global web of trafficking and coercion. On July 30, 2025, the UN marked World Day Against Trafficking in Persons by reporting over 200,000 documented cases between 2020 and 2023, with the true number believed to be far higher due to underreporting. According to the UNODC Global Report on Human Trafficking, 79% of trafficking involves sexual exploitation, predominantly of women and children. Nearly 20% of victims are children, with some regions — such as parts of West Africa — reporting figures as high as 100%.

Despite international protocols, trafficking remains a stubborn trade. It demands stronger laws, genuine enforcement, and unwavering commitment. Yet the TIP Report on Global Anti-Trafficking Gaps, published by the International Association of Women Judges, reveals that only one in ten trafficking cases brought to court results in conviction. Weak investigations, poor cross-border cooperation, and inadequate victim protection all contribute to this failure. If these numbers foreshadow what the Epstein files will yield, celebration may be premature.

Perhaps I am too grim. I hope I am. I hope the victims’ voices — whether tied to Epstein or to other predators — will be heard, honored, and felt. Their suffering must not be overshadowed by the sensationalism of “who did what.” Accountability matters, but it must extend beyond headlines. Naming and shaming is not justice. Justice requires courts, convictions, and systems strong enough to protect the vulnerable.

As a global society, we prove our solidarity with victims only when we prosecute predators, enforce laws, and invest in professional, adequate systems of justice. Only then can we stand together and say: we do not accept this behavior toward women and children. Only then can we send a message strong enough to deter those who would exploit.

The coming weeks will be a test — of our humanity, of our collective resolve. Fingers crossed we get this one right, and do not disappoint ourselves.

After the Headlines Disappear

What happens to the people behind the headlines after the headlines themselves fade away?

Last weekend I read a background story on the BBC app about a mother whose son had been stabbed to death. The article was published in the wake of a report on the rising number of teenagers in Britain carrying knives and the alarming increase in stabbings among young people. In response to her loss, she created a space where children can gather, play games, and leave behind their phones—and the hostility of the outside world. It was a story that offered a spark of hope amid the shocking realities of teenage life.

But mostly, stories are not followed up. Even this article was written because of a headline, not as a continuation of the story. I often wonder what is happening now, after the headlines have disappeared. What is the current situation in Sudan? Are governments truly following through on promises to combat femicide? Are the inhabitants of the Amazon still losing their battle against “progress”—progress demanded in the name of economic growth? How are the families of those slain coping? And what of the baby penguins I once saw in a documentary—are they still alive, or have the effects of global warming already claimed them?

We live in a world where crises unfold daily. News agencies deliver information, but it is often diluted, packaged into bite-sized morsels for easy consumption. Once digested, the public is fed a new flavor the next day, lest attention waver and audiences drift elsewhere.

Sometimes I wonder if I am the only one who thinks about these things. When I ask friends if they know how certain stories have developed, I am often met with blank stares or vague recollections: “Oh yes, I remember that—it was a long time ago, wasn’t it?”

Is the world simply too much for us to take on? Are we programming ourselves to delete not only information but also curiosity and empathy, because we lack the space to hold on to past events? Have we become addicted to the shock and awe of novelty, riding the adrenaline of fresh headlines, moving as a collective from one high to the next?

Psychology offers explanations. Cognitive Load Theory, developed by John Sweller, describes how our working memory is limited in capacity. When overwhelmed by too much information, we struggle to retain it in long-term memory. In the context of news, the sheer volume of daily crises makes it difficult to hold on to older stories. (https://practicalpie.com/cognitive-load-theory/) Meanwhile, Habituation—a basic form of learning—explains how repeated exposure to a stimulus diminishes our response. Applied to news, this means that as a story is repeated, our emotional and behavioral reactions weaken, reducing urgency and making it easier to forget.(https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-habituation-2795233)

In our age of rapid news cycles, this collective forgetting is almost inevitable. Highly emotional events may linger briefly, but each new crisis lessens the impact of the last.

And yet, forgetting does not absolve us. The inhabitants of the Amazon still face displacement from hydropower projects. More than 150,000 people have died in Sudan, with 12 million forced from their homes—the UN calls it the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. Families of victims continue to live with their grief long after the headlines fade.

Perhaps the challenge is not to remember everything, but to resist the pull of forgetting. If we take a step back and reflect on the news that has passed in recent months, we remind ourselves that while headlines are fleeting, the lives they represent are not. Atrocities remain, and attention is still needed.

We cannot save the entire world, but we can choose not to forget. By practicing sustained attention—by asking what happened next?—we honor the humanity behind the headlines. In doing so, we make space for empathy, and perhaps, for change.

A Season for Words

You know summer’s truly over when the rain begins — and doesn’t let up. Not a passing drizzle, but the kind that settles in, soaking the streets and dimming the sky for days on end. That’s when I feel the shift: not just in weather, but in mood, in energy, in the way my body moves through the world.

Autumn, for many, is a season of comfort. Fires lit. Wool sweaters pulled from the back of the closet. The slow build toward Christmas, then the hopeful pause of New Year’s Day. I understand the appeal — truly. But for me, those brief flickers of joy are swallowed by the long stretch of cold months that follow. I’m simply not built for sleet and snow, for the damp that clings to everything, including my bones.

Fatigue deepens. Sunshine becomes a memory. And yet — something else stirs.

Writing returns to me in the rain.

In summer, I’m pulled outward. The garden calls, the sun insists, and I answer. I bask, I breathe, I forget the discipline that writing demands. Inspiration scatters like pollen in the wind. But when the skies darken and the chill sets in, I retreat. Indoors. Inward. Back to the quiet companionship of my computer — a relationship that, despite everything, brings me joy.

There’s something about the rhythm of rain on the windows, the hush of grey mornings, that makes space for words. I write more. I write better. I write with a kind of honesty that only autumn seems to allow.

So here’s to the season of stillness. Of stories. Of showing up at the page, even when the world feels heavy.

This autumn I’ll be writing more often — both here on rosieglobal.com and on my newer blog, theunseenme.com, where I explore the realities of invisible disabilities. It’s a space I’ve long wanted to create: honest, reflective, and rooted in lived experience.

And if all goes well, I’ll be stretching even further — toward something that feels both thrilling and terrifying: writing a book. I don’t know if I’ll manage it, but I do know I want to try.

So thank you for being here. I hope these words offer you warmth, recognition, or simply a moment of quiet. Let’s see where this season takes us.

Disconnected: A Reflection on Empathy, Ethics, and the World We’re Becoming

As a child, I struggled to understand how adults could be so out of touch with the latest music hits, fashion trends, or the evolving societal landscape. I vowed never to become like them, those older individuals seemingly disconnected from reality.

Now, by my childhood definition, I am one of those older people. I find myself unfamiliar with most of the artists in the top 20 music charts, and I honestly cannot even put a name to an influencer. In my defense, I do make an effort to stay informed about fashion trends, although many are simply not suitable for someone my age. I have to admit: I’ve lost touch with certain aspects of modern culture.

What I find most disconcerting, however, is the sense that humankind has lost touch with itself and the world around us. I’m not just speaking of music or fashion, but rather the fundamental connections we share with other people, with nature, and with the ethical standards that distinguish us from other species.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has shifted dramatically. The virus has caused millions of deaths globally—over 6.9 million confirmed as of October 2023—along with widespread indirect impacts, including mental health crises. Reports indicate that the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders has skyrocketed during and after the pandemic, with studies from the World Health Organization showing a 25% increase in anxiety and depression worldwide. Moreover, the incidence of autoimmune diseases has risen substantially, reflecting the complex interplay between stress, immunity, and physical health.

We’re witnessing war in Europe, genocide in Israel, and the rise of extreme political and societal divisions. Our planet’s environment is deteriorating, with the World Wildlife Fund estimating that nearly 1 million species are at risk of extinction due to habitat loss, climate change, and pollution. The frequency and intensity of natural disasters, from hurricanes to wildfires, continue to escalate as climate change progresses- the UN reporting that climate-related disasters have increased fivefold over the past 50 years.

What we once considered ethical conduct, whether in politics, the workplace, or interpersonal relationships, has been tested and, frankly, has often failed. Social media has become a treacherous landscape, rife with misinformation, fake imagery, and polarizing narratives. The once free-spirited Western world seems to be succumbing to a climate of fear that stifles self-expression and meaningful dialogue about the issues that shape our lives. Instead of coming together, we find ourselves divided, manipulated by those who thrive on chaos and discord. In short, we are on a path toward de-civilization, drifting away from what it means to be human.

When did human interaction become transactional? Why do we expect something in return when we extend a helping hand? Why does my friend, who preaches humility and compassion in church, justify removing homeless people from public spaces because they make her “uncomfortable”? When did we start labeling those unable to work due to illness as ‘sloths’? When did social media influencers start shaping how boys view girls? Why are so many young people—especially women—struggling with depression? Why do we find ourselves in a culture of hate against those with opposing views? When did I become hesitant to read the news, fearing exposure to more tragedies or witnessing politicians prioritize money over empathy and ethics?

Perhaps I’ve lost touch with the world more than I realized. Maybe I’m still clinging to the mindset I had as a child—believing the world was beautiful, full of possibility, and waiting to be discovered. Is it outdated to advocate for human rights and gender equality? Is trying to save even a small piece of the world futile, because people fear drama and retaliation? Maybe I should step back and stop trying to understand a world I increasingly find baffling.

As a child, I would gaze up at the night sky, contemplating what lay beyond the stars. I watched fireflies dance in the dark, creating a magical display for those who took the time to notice. I felt the earth beneath me—its weight, its history, its power. The world was something to admire, to explore, to be in awe of. It pulsed with life, and I could feel it in every fiber of my being.

Even though the stars are less visible and firefly populations are dwindling due to environmental changes, I can still relive those cherished moments from my childhood, reawakening the same feelings I experienced lying on the ground decades ago. Perhaps that’s what we all need to do—lie on the earth, look up at the stars, and reconnect with who we once were. Maybe, just maybe, in doing so, we can feel the earth beneath us and remember what it means to be human again.

From Tragedy to Transformation: The Fight for Women’s Safety

Last week, in the Netherlands, a 17-year-old girl was murdered on her way home after a night out with friends. Aware that she was being followed, she called the emergency number and provided her exact location. Although a police car was dispatched immediately, it was too late. She was found in the bushes, violently murdered with numerous stab wounds.

This incident unleashed a tremendous wave of shock and outrage within Dutch society. Politicians pledged to create new policies aimed at improving the safety of women and girls. A movement called “We Claim the Night”, based on the international movement “Reclaim the Night”, emerged, raising substantial funds through crowdfunding for a campaign to ensure women’s safety during the evenings and nights. Remembrance gatherings were held, and a moment of tribute was observed during soccer matches at the 17th minute, accompanied by applause to honor Lisa, the young victim.

While I commend those who advocate for the safety of women and girls, I approach these initiatives with a degree of cynicism. The shock and outrage are genuine, yet the reality is that the safety of women and girls has been compromised for centuries. In modern times, the situation has not improved; if anything, women are just as vulnerable to violence as they were in 1610—perhaps even more so.

I recently read The New Age of Sexism by Laura Bates, which I believe is essential reading for everyone. She provides a detailed account of how misogyny and violence against women have taken on new, dangerous dimensions in the digital age. Issues like gang rapes in the metaverse, deepfake pornography of women and children, and online sexual abuse in schools are on the rise. Tech companies are aware of these problems yet choose to remain inactive, allowing boys and men to believe that it’s acceptable to torment women. The behavior tolerated in the digital world is just as harmful to women and girls in the real world and, even worse, it serves as a learning curve for predators. Research shows that violent behavior towards women in the digital realm often foreshadows real-world violence.

When publicly accessible sites allow revenge porn to flourish, where bitter men can share not just explicit photos of their ex-partners but also their addresses and personal information, it’s clear something is wrong in our society. When 13-year-old boys create and distribute deepfake nude images of their classmates, we must acknowledge fundamental issues in how boys are raised. Furthermore, the idea that it’s acceptable to mutilate sex doll robots to prevent violence against real women ignores the underlying aggressive tendencies these men exhibit, which may one day escalate to real-world violence.

According to Laura Bates, major tech developers—often wealthy white men—are hesitant to implement safeguards for protecting women and girls from abhorrent behavior. They shift the responsibility onto women, expecting them to protect themselves. If something goes wrong, they are told to go to the police. Yet proactive measures to prevent bad behavior are not prioritized, as that would impact their revenue. Billions of dollars are generated from apps that facilitate deepfakes and AI-driven games where (predominantly male) users act without consequence, creating virtual worlds where women and minorities are mistreated.

As we speak, a major tech company is building a metaverse, an alternate virtual world where we go to work, shop, go to school, and create social communities. If tech companies indeed continue on this path, we may soon find ourselves living much of our lives in the metaverse, a rapidly expanding realm that lacks the foundation of equality and safety for its users. What kind of world will it be when we are forced to engage with it? It is not a world I want to inhabit.

Our future AI world will likely amplify issues from our ‘real’ world, potentially leading to more violence against women and other minorities. Can moderators effectively filter out criminals? Will there be consequences for their actions? Will they be able to intervene in time to protect a woman in distress?

Whether we inhabit our physical world or a virtual one, violence against women and minorities will not cease just because a few people pay attention during isolated incidents, like the tragic murder of a promising 17-year-old. We must care equally for the safety of nameless women in Sudan who face violent rape and murder, and for the 10-year-old girl in Spain whose fake nude photos circulate in her school. On a global scale, we need to teach boys and men that violence is unacceptable, that women possess rights, and that they deserve respect. Women with opinions or who stand up for themselves and others are not threats; they enrich our society. Women should be able to dress as they wish and walk through a park at night, confident that they will be valued and safe from harm.

Will we ever fully eradicate hatred and violence toward women? I fear the answer is no, but we can reduce it. We must punish those who disregard fundamental rights and create a safer world than the one we currently inhabit or are heading toward. Achieving this requires courage, determination, and collaboration among lawmakers, politicians, influencers, tech leaders, the judicial system, and individuals alike – on a global level. Only then, perhaps, can Lisa’s legacy inspire a future where all women feel safe.

Keys in Hand: The Reality of Women’s Safety After Dark

This month, Dutch research bureau CBS (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek) published findings on gender differences in perceived safety. Almost half of the young female population (ages 15 to 25) report taking alternative routes home to avoid ‘unsafe places.’ Even among older women, the numbers remain substantial, with 30% of those aged 65 and up doing the same. Men, by comparison? Around 20%—across all age groups. In addition, 45% of all women say they fear becoming a crime victim in their own neighborhood.

These numbers were considered newsworthy in the Netherlands, as they should be. When nearly half of the female population doesn’t feel safe in their own streets—and even change their route home to avoid danger—there’s a problem.

Yet even acknowledging the severity of these statistics, I find them low. Most women I know don’t feel safe on the streets, especially in the dark or when walking alone. We know to keep our keys ready—for quick entry or as a weapon. We’re taught to yell “fire!” instead of “help!” because people are more likely to respond. We plan our routes, steer clear of tricky areas, let men pass when they’re behind us, glance into shop windows to check who’s nearby, and constantly assess risk. It’s second nature. Given all that, 45% feels like an understatement.

That got me wondering—what are the numbers in other countries?

According to Gallup’s 2023 Crime Survey, over 50% of women in the United States report feeling unsafe walking alone at night, compared to just 25% of men. Studies show that women tend to scan for dangers like bushes and dark corners, while men focus on the path ahead. In Great Britain, 63% of women feel unsafe walking alone at night, with the 18–25 age group scoring remarkably high at 81%. Parks and open spaces after dark? Around 80% of British women say they feel unsafe.

In Germany, 48% of women feel unsafe in their own neighborhoods. In France, surveys show 54% of women feel unsafe walking alone at night. Australia sits at 40%. In India, a startling 79% of urban women report harassment or violence in public spaces, and Brazil tops the list with 89%.

So what about Scandinavia—known for progressive gender policies and high levels of gender equality?

In Sweden, 34% of women say they feel unsafe walking alone at night. In Denmark, that number is 22%, and Norway reports just 13%. On an emotional level, any percentage is too high, but statistically speaking, women in Scandinavia perceive less danger than those in the rest of Europe, the U.S., or the Global South. Why?

Many government reports point to cultural and societal norms. In countries with entrenched patriarchal structures and gender inequality—like India and Brazil—harassment and violence are more frequent. Even in places with legal gender equality, such as Western Europe and North America, underlying cultural attitudes still shape both violence and the fear it instills.

This theory may explain Scandinavia’s relatively low fear levels, where women enjoy both legal rights and cultural equality. According to The Perspective, Northern European women have higher trust in law enforcement and stronger support systems. This encourages reporting and reduces anxiety. When you believe the police will take you seriously—and the courts will hold attackers accountable—you naturally feel safer. It may also discourage violence in the first place.

That said, Scandinavia isn’t without contradictions. The so-called ‘Nordic Paradox’ refers to the relatively high rate of intimate partner violence in these countries despite their strong gender equality. Some researchers suggest that female empowerment can provoke backlash from entrenched masculinity norms. A girl just can’t catch a break.

“Creating equality for women doesn’t mean diminishing men’s worth.” — Equality isn’t a zero-sum game

The Path Forward

Can public policy help shift these numbers? In theory, yes. Governments have invested in safer infrastructure—better lighting, expanded CCTV—and educational efforts that promote respect and gender equality. Safety charters, community patrols, and venue staff training programs have all been introduced. While these efforts have raised awareness, many studies show that actual safety statistics haven’t improved much.

The truth is this: female safety—at home and in public—is a real issue. Statistically, crime against women is substantial. These realities fuel the fear women feel, especially in quiet areas and after dark. That fear isn’t irrational—it’s based on experience, and often passed down from mother to daughter. We’re taught early on to fear sexual assault, physical violence, and emotional abuse. By the time we’re grown, it’s second nature. We don’t like it, we don’t accept it, but we’ve learned to live with it.

So here’s my question to societies around the world: when we hold the next baby girl in our arms, do we really want the first message she receives to be one of fear? To be afraid of the dark, afraid of strangers, afraid to walk through her neighborhood alone? To be afraid of the world for the rest of her life?

Not in my world.

“You are beautiful, you are smart, and you are worthy of a life without fear.” — What every girl deserves to hear

In my world, we say: you are beautiful, you are smart, and you are worthy of a life without fear. We teach boys that empowering girls doesn’t mean shrinking themselves. We teach men that love and respect are stronger than hate and violence. And we push governments to act when violence does occur—to prosecute, to protect, and to prevent. We aim for a world where keys are meant for opening doors and not as weapons.

We refuse to accept anything less.

Who wants to join me in my world?

The Absence of Empathy: When Poverty Becomes Policy

“Evil, I think, is the absence of empathy.” — Captain G.M. Gilbert, Army psychologist at the Nuremberg Trials

Gilbert observed this moral void among Nazi defendants, noting their inability to connect emotionally with other human beings. Evil, then, may not stem from a desire to harm but from an unwillingness—or incapacity—to care. It is not always malicious action that defines evil, but a haunting indifference to suffering.

This idea weighs heavily as, while I write this blog, the U.S. Senate debates what some hail as the “Big Beautiful Bill” and others condemn as the “Big Ugly Bill.” Regardless of where one stands politically, the consequences of this legislation are monumental—particularly for those most reliant on governmental support.

If enacted, 12 million people could lose Medicaid, their only access to health insurance, according to projections from the Congressional Budget Office and several health policy organizations. To remain eligible, individuals may be required to work up to 80 hours per week and re-apply every six months.

Reforms to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) would transfer funding responsibility to states and impose work requirements on childless enrollees—measures that threaten the lifeline of over 40 million low-income Americans.

What disturbs me is not the political debate, but the absence of a deeper question: What will this mean for the future of our society?

In 2023, 11.1% of the population—roughly 36.8 million Americans—lived below the poverty line, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Nearly 29% of the population lived in low-income families, defined by the Pew Research Center as earning less than two-thirds of the national median income.

In 2022, about 12.8% of Americans experienced food insecurity, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. On a global scale, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports that the U.S. has the highest poverty rate among its 26 most developed member countries. Further, a UNICEF study ranks the United States second in relative child poverty, surpassed only by Mexico, when measured against 35 of the world’s richest nations. The weight of these statistics is not just economic—it’s existential.

Childhood poverty isn’t a temporary hardship. It’s a chronic condition with lasting consequences. The longer a child lives in poverty, the less likely they are to escape it. According to Ballard Brief, children who grow up poor are up to 46% more likely to remain poor into adulthood. Every year spent in poverty decreases the chance of escaping it by nearly 20%. This isn’t just misfortune. It’s a broken system of intergenerational inequity.

And now, we’re preparing to cut deeper into the support structures these children rely on.

The familiar refrain is: “Children are our future.” But what kind of future are we building if one-third of our children are undernourished, undereducated, and underserved?

Children in low-income families have limited access to quality education and nutritious food. Healthcare is a luxury, and safe environments are not guaranteed. The playing field isn’t just uneven—it’s obstructed. They are given fewer tools, fewer chances, and less support to climb toward a stable adulthood.

The bill currently under debate doesn’t just trim budgets—it trims hope. By withdrawing investment in childhood development, we are not just ignoring our most vulnerable; we are sabotaging society’s long-term potential.

So, what is the alternative?

We invest. We level the playing field. We provide children—regardless of income—with access to safe schools, nourishing food, sports programs that heal hearts and build character, and environments that spark ambition instead of extinguishing it. We make sure their caretakers are well nourished and can provide a stable environment for them. We invest in their communities, making them safe places to love and thrive.

This kind of investment requires compassion, and yes, it costs money—lots of it. But then, what kind of revenue do we value more? Extra profits for the already privileged or a robust, equitable society?

Empathy is not weakness. It’s strength. Compassion is not charity. It’s policy. And societal evil? It isn’t born from malice—it grows in the shadow of indifference.

Waves of Goodbye: Honoring My Mother

Today is my mother’s birthday. Her first since her passing last year. For the first time in my life, there’s no phone call to be made, no present to be bought.

Losing a parent is one of life’s most difficult chapters. In my mother’s case, it happened more than once. She had Alzheimer’s disease, and so I lost her in waves—each wave pulling another piece of her back to the ocean.

In the final years of her life, she no longer knew who I was. Nor my children. She had forgotten her husband—my late father—her childhood, her dreams, her life. She became a kind, quiet woman in a wheelchair, smiling whenever someone greeted her or when the sing-alongs began in the care home’s rec room.

I can’t say her passing was a relief for me. I had adapted to her condition, found a way to still enjoy our time together. But for her, death was a release. She had developed cancer that had spread through her body, bringing her immense pain—especially in those final days. Her passing, quite literally, set her free.

Although this is my personal story, I know it’s not unique. According to the World Health Organization, 57 million people worldwide were living with dementia in 2021. That number is expected to rise to 152 million by 2050. Around 10 million new cases are reported every year.

Just imagine—millions of people who no longer remember their parents, their first love, their dreams. People who forget who they were, who their children are, who lose their ability to communicate. Their bodies remain, but their personalities and identities fade, leaving behind a shell inhabited by someone we no longer fully recognize.

When my mother passed, I kept thinking about the girl she once was. What had she dreamed of becoming as a teenager? What had she imagined for herself—and for us, her children? Many of those dreams didn’t come true. And I grieved that. I grieved not only her death, but the unlived life I felt she deserved.

On this first birthday since her passing, I still wish more had been possible for her. But over the past months, I’ve begun to release that sorrow. I’ve found comfort in the belief that she was at peace with her life as it unfolded. That the absence of some dreams made room for real happiness in unexpected places.

She never made it to France, no. But she did make memories with us on countless trips to the Wisconsin Dells—and I believe she cherished that even more.

It’s a shame she couldn’t remember those joyful moments. But just because she forgot them doesn’t mean they didn’t exist. She lived. She loved. She laughed, fought, reunited, cried. She was a beautiful woman—inside and out. And even when she couldn’t remember who she was, we did. She couldn’t preserve her identity, but we carried it for her. In all the times I said goodbye to parts of her, I didn’t yet realize that she wasn’t disappearing—she was taking up residence in my memory. She lived on in me.

Today I honor the woman who brought me into the world and raised me into the woman I am. The woman who shone her unique light into the world, a light that now lives on in those she touched.

And I honor all those living with dementia—patients, family members, caregivers, friends. You are walking a path no one should have to face alone. I hope, wherever you are on it, you find peace.

Happy heavenly birthday, Mom. My gift to you is this: I remember.

Accessibility Is More Than Ramps: Living with Invisible Disabilities

On Monday, I shared thoughts on the lived experience of disability. I unexpectedly received messages of gratitude from readers across the board. There is so much quiet hurt in the world—people feeling misunderstood, or navigating conversations about illness without care or compassion.

Yesterday, I had a conversation with a rehabilitation doctor. He asked whether I find it difficult to communicate what I go through as someone with an invisible disability. I explained that it’s not so much the ability to articulate it—that part, I’ve honed. The difficulty lies in being understood. People don’t always have the shared experience needed to grasp what the words truly mean. For example, chronic fatigue isn’t simply “being tired.” Tiredness can be resolved by rest. Chronic fatigue is unpredictable, invasive, and unrelenting.

I told him: the only way to bridge the gap is to shine a light on what invisible disabilities are, to inform the broader public about the challenges we face, and to make it part of our social conversation. Once we’ve done that—then ask me again if it’s hard to communicate what I go through.

More information and more visibility are urgently needed. And I’m more than willing to provide it. Today, I want to start by exploring what often goes unseen—what’s misunderstood, overlooked, or dismissed. Invisible disabilities can shape every aspect of a person’s life and may prevent full access to the world around them.

When people think of accessibility, they often picture ramps, lifts, or wide doorways. Those are vital—but accessibility goes far beyond bricks and concrete. For those of us living with invisible disabilities, access might mean flexibility with time. It might mean freedom from harsh lighting, loud noise, or overstimulating environments. It might mean understanding that energy is not just limited but also unpredictable, and that “pushing through” can have lasting consequences.

Access means being able to exist, participate, and belong—without having to constantly justify your needs.

In modern life, we’ve grown used to explaining how we feel, defending our thoughts, and using words to build bridges of understanding. But here’s the golden rule of communication: the message must be received and understood by the other person. If I tell you my dog has blue hair, but you don’t know what “blue” means, you’ll miss the point. So when I say that fatigue is a debilitating part of my condition, someone might hear “fatigue = tired,” and think, “I get tired too, but I push through and go to bed early—why can’t you do the same?”

That’s where miscommunication starts. And once misunderstanding sets in, it often leads to misplaced accountability and judgment.

We live in a culture that values performance and productivity. We hold people accountable for what they do—which, in many cases, is entirely reasonable. But what happens when someone is judged by standards shaped by assumptions? When a person is scrutinized for not working, simply because their disability isn’t visible? Or asked to explain why they can function one day and not the next?

The truth is, society isn’t designed with invisible challenges in mind. If your condition isn’t visible, many assume you’re fine. But this assumption erases the labor it takes just to show up. It dismisses the brain fog, the pain, the anxiety—and the constant effort to mask it all in order to be seen as “normal.”

And that masking itself is exhausting. The pressure to be believed, to seem capable, to avoid suspicion—it all adds to the weight we carry. It fuels stress, deepens isolation, and increases the distance between us and the world.

So how do we begin to make space for invisible disabilities? How do we make society more accessible?

It begins with a shift—from suspicion to trust. That’s not a small ask. In today’s world, it’s a paradigm shift. But it’s not about special treatment. It’s about equal footing. It’s about creating spaces where people don’t have to fight to be believed before they’re offered support.

How do we spark that shift? We start by listening. Without judgment. With open hearts. With a willingness to be wrong and to grow. We start by saying, “Even if I haven’t lived it, I believe you.” We start by giving people what they need to thrive—and valuing them for who they are, not for how much they produce.

Not everyone’s experience looks the same. But every voice deserves to be heard. Let’s listen to those voices. And let’s make space—for all of us.

Not Just Ill: Redefining My Chronic Condition

Dealing with an invisible chronic illness isn’t easy. Beyond the fatigue, physical pain, and brain fog, there’s another layer of struggle: people don’t see how unwell you are. They see the outside—maybe a sun-kissed face, some makeup, a well-put-together outfit, a warm greeting—and they draw their own conclusions.

They see you show up at a birthday party and think, “She must be doing better.” They don’t know that you had to sleep for two hours beforehand and will now be in bed—or glued to the couch—for the next three to five days because you went. They ask how you’re doing, and you say, “I’m fine.” Not because it’s true, but because sometimes you’re simply tired of talking about being sick.

In my case, I really do get sick of talking about being sick.

So yes, people sometimes assume I’m better than I am. Some may even think I exaggerate my illness. After all, lots of people are tired—and they still get up and go to work. Why can’t I?

It’s okay. I understand how society copes with things it can’t see or make sense of: it labels, defines, reduces. It filters experience through its own lens so the unfamiliar becomes manageable. Living with an invisible illness for the past five years has taught me to tune out those voices. I’ve learned to define myself based on my own sense of worth, not the value placed on me by others.

When ‘Illness” becomes “Disability”

Still, that definition of self took a jolt last week. While doing research for my book on invisible illnesses, I came across something unexpected: several major health organizations now classify my condition as an invisible disability. That word stopped me cold.

According to the World Health Organization’s World Report on Disability (2011), disability is defined using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which breaks down functioning into three interconnected categories:

- Impairments: problems with body function or structure

- Activity limitations: difficulties in executing tasks or actions

- Participation restrictions: challenges with involvement in life situations

Disability, then, isn’t about one diagnosis—it’s about how health conditions interact with personal and environmental barriers to limit engagement in life. The ICF uses neutral language and doesn’t distinguish between physical or mental origins. If your condition affects your ability to function and participate fully, it qualifies.

Suddenly, I found myself staring at the screen thinking: Wait. You mean I’m disabled?

The word “disability” has always carried a specific image in my mind—something concrete, visible, undeniable. I never thought to put my illness, or any chronic illness, in that category. Illness felt like a challenge, something to fight, to manage, to overcome. Disability felt… definitive. Permanent.

But that’s the thing: having a chronic illness is a disability. It impacts my ability to participate in society. It limits what I can do. It interferes with basic functioning. And it’s real, whether people see it or not.

Seeing the Unseen

According to Hidden Disabilities Sunflower, one in six people globally live with a disability. Of those, an estimated 80% are non-visible. That’s over a billion people, most of them unseen—and undervalued. Yet every one of them has something meaningful to offer. We want to engage. We want to be included. We deserve the space to contribute.

Maybe “disability” is a better word after all. “Illness” often implies recovery is coming, or should be. There’s an unspoken apology in it, a pressure to heal. “Disability,” on the other hand, demands society’s acceptance. It calls for accessibility, empathy, and policy that affirms our worth.

So here I am: a woman with an invisible disability. And an awful lot to give—to those who acknowledge my boundaries, honor my integrity, and respect my value.

Maybe it’s time we all reconsider what disability really looks like—and who we assume doesn’t carry it.

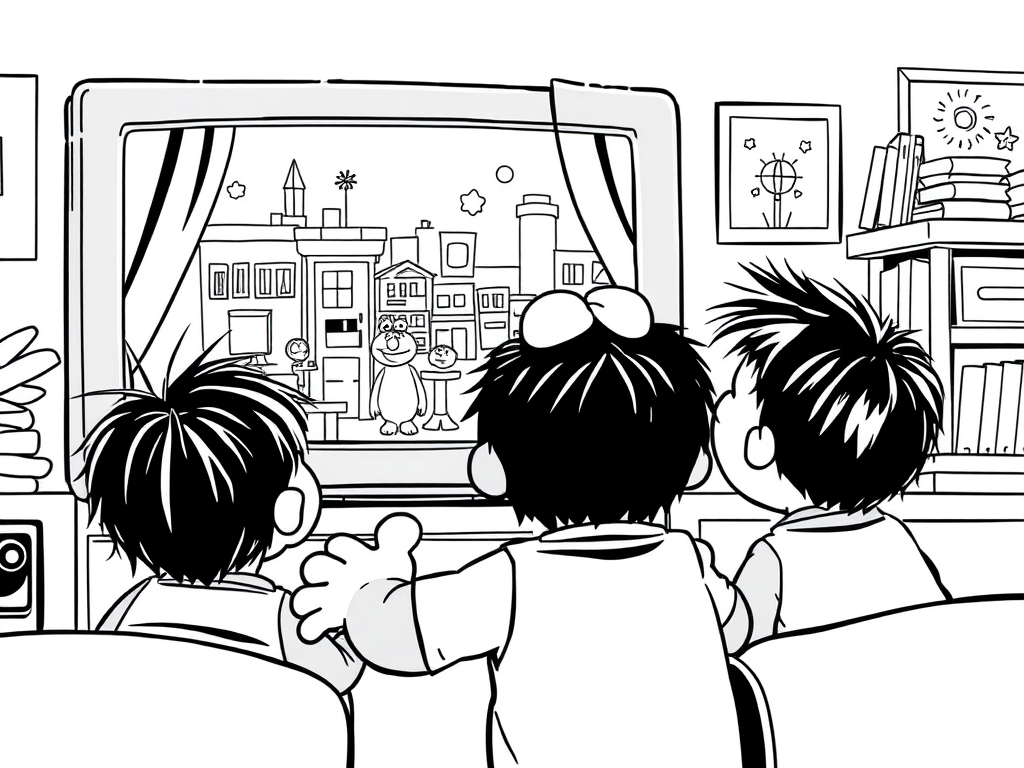

Sunny Days Restored: The Fight to Keep Sesame Street Accessible

For the first time ever, I find myself saying: “Hurray for Netflix!”—because it just might have saved Sesame Street.

Like many American children, I grew up watching Sesame Street. As a first-generation viewer, I was captivated by Big Bird, learned to count with Count von Count, and happily sang along with Ernie to Rubber Ducky. My fondness for that little yellow duck runs so deep that I still have its birthday marked on my calendar—January 13th, for those who want to celebrate too! But beyond the songs and characters, Sesame Street gave me something even more valuable: the foundational knowledge, social skills, and essential tools I needed to prepare for kindergarten.

The Vision Behind Sesame Street

The idea for Sesame Street was born in 1966, when Joan Ganz Cooney, executive director of the Children’s Television Workshop, and Lloyd Morrisett, vice president of the Carnegie Foundation, envisioned a children’s television show that would harness the power of TV for education. As Cooney described it, they wanted to “master the addictive qualities of television and do something good with them” (Michael Davis, Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street).

At a press conference on May 6, 1969, Sesame Street was officially announced as an innovative program that would use commercial television techniques to teach young children. By blending live-action sketches, animated cartoons, and puppetry, the show would introduce preschoolers to essential concepts—letters, numbers, vocabulary, shapes, and reasoning skills. Repetition throughout each episode would ensure young audiences remained engaged while absorbing important lessons. The name Sesame Street itself was chosen to evoke the magic of discovery, inspired by the phrase “Open Sesame!”—suggesting a place where exciting things happen.

When the show premiered on November 10, 1969, its mission was clear: to prepare children for school, particularly those from low-income backgrounds who might not have access to early education. By 1996, a staggering 95% of American preschoolers had watched it by age three, and by 2018, it was estimated that 86 million Americans had grown up with Sesame Street.

The Fight for Accessibility

From its inception, Sesame Street aired on PBS, a public broadcasting network offering free programming. This accessibility was crucial for low-income families who depended on the show as an early education tool. However, when the Trump administration reduced funding for PBS, Sesame Street faced an uncertain future. The potential loss of free access meant that the very children who needed Sesame Street the most could lose their connection to its invaluable lessons.

The decision to slash funding for PBS was deeply distressing—not just because it affected educational programming, but because it signaled a fundamental misunderstanding of how critical early childhood education is for children who cannot afford preschool. These kids wouldn’t just miss out on learning letters and numbers—they’d lose the examples of kindness, diversity, self-worth, and the power of positive social interactions. For many, Sesame Street is their only exposure to these essential developmental values.

Why It Matters

In a world increasingly divided by socio-economic disparities, investing in early education is not optional—it is essential. Children need education, healthcare, and stable environments to thrive and grow into balanced, engaged citizens. These future generations will shape our society, and it is our responsibility to ensure they have the tools to do so.

And that’s where Netflix comes in. By stepping up and ensuring PBS can continue broadcasting Sesame Street, Netflix has done something truly meaningful. It has recognized the importance of preschool education for disadvantaged children and preserved a program that has enriched young minds for over five decades.

So yes, Netflix—you’ve found your way to Sesame Street, and in doing so, you’ve helped keep its doors open for those who need it most.

Lost in Expectations: The Growing Mental Health Crisis Among Young Women

Some time ago, I ran into an old acquaintance I hadn’t seen in years. As we engaged in the expected exchange of updates, I asked about her eldest daughter. She told me her daughter was doing well—she had recently married—but when I asked whether she planned to have children soon, her answer was sobering: “No, she’s too concerned about what’s happening in the world. She feels it isn’t a safe place to have children.”

Her daughter doesn’t live in a war-torn or impoverished country. She lives in Western Europe, holds a stable job, and comes from a loving home. Yet, despite having every material advantage, she fears the future enough to forgo motherhood.

At another social event, I spoke separately with two young women in their early thirties, both struggling with mental health issues. They shared their fears about not being able to function in today’s world, burdened by pressure and uncertainty about their futures.

In yet another conversation, a friend’s acquaintance told me she had to force herself to leave the house because agoraphobia was creeping in. She was seeing a mental health specialist to address her anxiety and other struggles.

These encounters left me deeply unsettled. Mental health issues, especially among young women, are nothing new. History reminds us of the struggles faced by Virginia Woolf, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Sylvia Plath—women who grappled not only with personal turmoil but also societal pressures. More recently, we have seen reports detailing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on younger generations. Yet, I can’t shake the feeling that something more is happening. It seems that more young women than ever before are struggling to cope.

The Statistics Speak Volumes

According to a 2017 report by Mental Health UK, women are three times more likely than men to experience common mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. In 1993, this risk was twice as likely, meaning the disparity is growing. Rates of self-harm have tripled since 1993, and young women are three times more likely than men to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. Additionally, anxiety-related conditions are most prevalent among young women.

These statistics are mirrored across Western Europe and North America, and numbers have continued to rise since the pandemic. But why do women experience more mental health challenges than men?

The Weight of Modern Pressures

The reasons behind this crisis are complex and multifaceted. Biological factors such as hormonal fluctuations play a role, but socio-economic stressors are equally significant. Poverty, workplace inequality, physical and sexual abuse, and the pressures of caregiving all contribute to heightened levels of anxiety and depression.

Yet these issues have existed for centuries—so why have rates increased so dramatically in recent years?

Professor Jayashri Kulkarni from HER Centre Australia at Monash University suggests that modern young women face a unique set of challenges in navigating their identities, including:

- Career and educational aspirations

- Body image insecurities

- Sexual and relationship expectations

- Social network development and maintenance

Social media exacerbates these pressures by fostering unrealistic comparisons and misinformation. Many young women engage in digital relationships that can deepen feelings of isolation and disconnect from reality.

Additionally, loneliness is an often-overlooked factor. Kulkarni notes that young women experience profound feelings of emptiness more commonly than acknowledged. The pandemic lockdowns intensified this issue, cutting them off from critical support systems and social outlets.

Surveys measuring post-pandemic mental health reveal increased rates of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and substance addictions—especially among young women. Though the restrictions have lifted, their emotional wounds continue to linger.

A Generational Struggle

The pressures faced by young women today differ from those of previous generations. While women have long balanced multiple roles, today’s digital world imposes new standards—curated beauty ideals, relentless public scrutiny, and a culture where mistakes can be magnified and immortalized online. Unlike before, there’s little room for imperfection.

So, how do we help this generation of smart, creative, compassionate, and talented young women?

We start by reminding them that they are more than enough. We offer support not by merely asking what they need, but by showing up—attuned to their struggles, ready to help in ways they might not yet articulate.

We foster stronger communities so that no one faces their burdens alone, making caregiving a shared responsibility rather than an isolating duty.

We tell them it’s okay to stumble, that they are beautiful in every facet of their existence—flaws and all.

Most importantly, we hold them close in our hearts and refuse to let them slip through the cracks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.